Background

In the 1920s, anthropologist Verne Frederick Ray began his lifelong relationship with the Plateau peoples living in northeast Washington State (USA) and recorded a story from a Sanpoil-Nespelem woman about the time when she was young and a minor fall of ash, probably from the Mt Baker volcano, occurred along that part of the Columbia River valley where her people lived. So fearful were these people of the volcano and what might happen next that they did not gather food for the winter, as was their customary practice, but “instead prayed and engaged in ritual dancing” (Fast, 2008, p. 134). While today we might be quick to dismiss such practices as superstitious, at that time they are likely to have been considered effective tools for averting risk, grounded in people’s understandings of the world.

This paper argues that our tendency to dismiss ancient risk-management practices of this kind as worthless in today’s world is misguided, incurious and consequently missing any opportunity to inform modern science-based practice. This situation is amplified by both “the tyranny of literacy” (Nunn, 2018, p. 30), the idea that literate people generally instinctively undervalue knowledge that is not written but only known orally, as well as the demonstrably spurious proposition that cultural practices like ‘dancing’ evolved solely as a form of artistic expression rather than having once been a vehicle for storing and communicating important knowledge in pre-literate contexts (Kelly, 2015; Nunn et al., 2022; Stratford, 2022).

This paper begins with a reflection on the contrasts between risk management in modern and pre-modern societies. There follows a discussion of ancient practice likely to have been systematic and enduring in the latter and deep-rooted in people’s world views and their experience of risk in particular places. A discussion of how ancient practice of this kind might enhance the effectiveness of contemporary risk management concludes this paper.

Managing risk in ancient and modern contexts

We live in risky places where things sometimes happen that affect our health and livelihoods, sometimes even threaten our survival. And because like all living things, we appear to be programmed to have our bloodline endure,[1] we seek ways to avoid or minimize such risks. Today, there is a tendency to think of risk management as something to be learned from a textbook, something that needs to be taught anew to each successive generation to help their members survive in an unpredictable world and in turn allow them to inculcate the next generation (Lallemant et al., 2023; Rajabi et al., 2022). It is often implicitly assumed that risk management of this kind was enabled by literacy, the ability of people to acquire knowledge through reading, and that pre-literate societies were handicapped in this regard, fortunate to have survived as they did. This is demonstrably incorrect, as shown by studies of oral societies that were able to acquire, organize and effectively communicate vast quantities of diverse knowledge inter-generationally, sometimes for thousands of years (Nunn, 2018; Sugiyama, 2017). Pre-globalization societies were equally as risk-aware and risk-averse as today’s globalized ones.

A key difference was the scale of risk awareness and risk minimization. Whereas today, many strategies for risk avoidance and coping are generic and applicable globally (Jensen et al., 2015; Nielsen et al., 2024), such strategies were localized in the pre-globalization past.

They had been developed, often over millennia, by groups of people living in particular places. They derived from and applied to the geography of those places, and were filtered through the world views of the people who lived there (Calandra, 2020; Hilhorst et al., 2015); examples are given in the next section.

Both approaches were appropriate for the times and places where they evolved. Today there are many commonalities between sources of risk, including infectious diseases and wildfires and oil spills, that can be better managed at a global level in a world where people are unprecedentedly mobile and interconnected. In the past in contrast, people were far more isolated and less mobile, meaning that place-specific local strategies for risk awareness, avoidance and minimization were more appropriate.

Over the last 200 years, the clash between the modern/global and the past/local has not generally seen the latter treated sympathetically, traditional practices often hailed as anthropological curiosities representing manifestly risible understandings of the world. Good examples come from phenomena like dancing and performance, poetry and song, even art (James & Williamson, 2020; Nyland & Stebergløkken, 2020). All these originated as methods for the effective communication of information in pre-literate societies in which older people recognized that the ability of younger members of their tribe to understand and retain all the knowledge being offered to them was essential to their survival (Sugiyama, 2021). Thus in every pre-literate society, storytellers would convey information in ways that engaged their audiences, by singing and reciting, by dancing and mimicking, by painting meaningful designs on rock walls. Once mass literacy spread, people forgot what these cultural phenomena had been intended for and repurposed them as art.

Ancient practices for risk management

Some of the most profound localized risks to human survival come from catastrophic (rapid-onset) events and include volcanic eruptions and earthquakes, discussed below in the first two subsections. These accounts show that pre-modern societies had a deep-rooted understanding of why such phenomena occurred, what their precursors were, and what effects they might have on peoples living in a particular place. Ancient societies also evolved ways of avoiding such disasters.

The best examples of slow-onset disasters are those attributable to climate change, especially sea-level rise, which affected pre-modern societies in similar ways to those which modern humans are experiencing. These are discussed in the third subsection below and show that the ancestors of modern people in many parts of the world exhibited an awareness of climate change, experienced anxiety about climate change, and eventually found ways to cope with climate change – just like today.

Traditional responses to threats of volcanic eruptions

People living near active volcanoes sometimes resist moving elsewhere when an eruption threatens, often because they are living on land whose fertility is enviably high, often because they have faith in their own culturally-grounded understandings of the threat to keep them safe (Donovan et al., 2012; Griffin & Barney, 2021; Lavigne et al., 2008). To avoid being affected by eruption, proximal communities often seek to develop and sustain relationships with the deities they believe to control volcanism, following certain rituals, abiding by particular taboos, and making sacrifices to assure their safety.

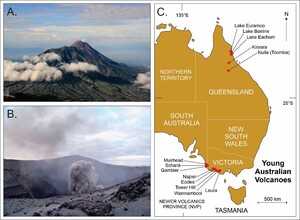

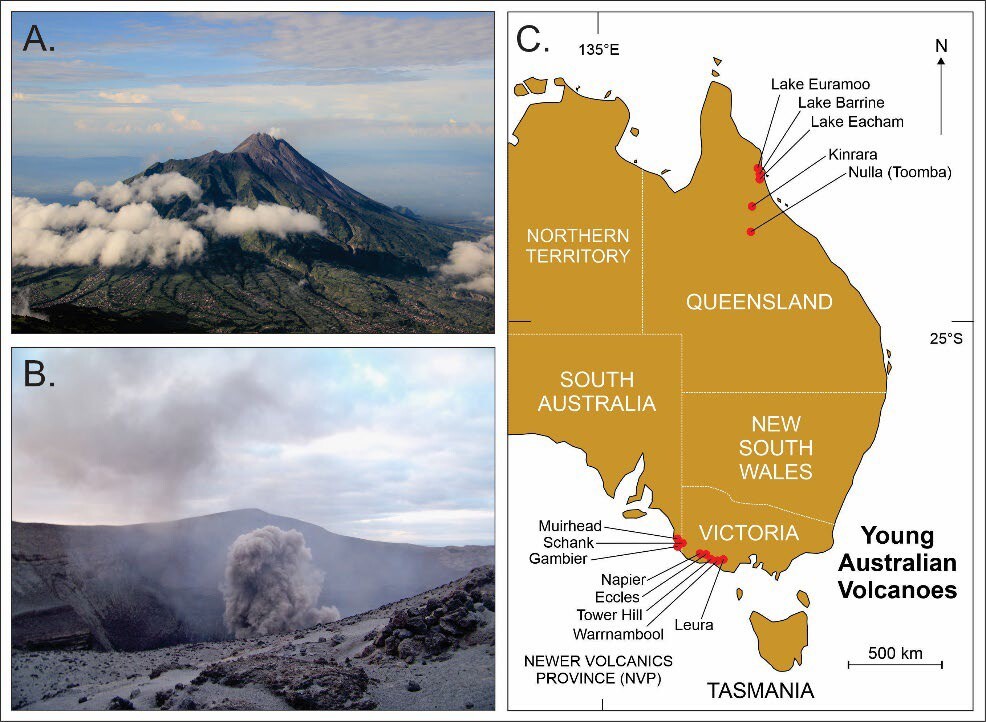

Good examples come from the active volcanoes of Indonesia (Nazaruddin, 2022). Around Mt Merapi, for example, many residents believe that ‘a spirit kingdom’ exists within the volcano and that people can live in harmony with its fractious inhabitants only by performing traditional Javanese rituals known as slametan involving prayers and the offering of foods (Figure 1A). In return, before an eruption occurs, the spirits would inform the designated human interlocutors (juru kunci) about when the eruption was due and which places it would affect, information (wisik) communicated in the form of dreams or animal behaviours that allowed people to avoid harm.

A comparable situation applies to the active volcano named Yasur on Tanna Island in Vanuatu (Southwest Pacific) where local people have consistently rejected unfamiliar external risk-management on the grounds that it conflicts with their traditional beliefs (Figure 1B). The Tannese hold that an eruption of Yasur is “the expression of anger by their ancestor because of a wrong action of community members” (Niroa & Nakamura, 2022, p. 1). When Yasur shows signs of imminent eruptive activity, community representatives will visit the rim of the crater, sacrifice a white chicken and drink kava to be able to communicate with the spirit of the volcano and sooth his anger. Such practices almost certainly existed in similar Pacific Island situations even though only oral traditions of volcanism remain here; examples come from Fiji, Hawaii and Samoa (Fepuleai et al., 2017; Lancini et al., 2023; Swanson, 2008).

Within the human history of Australia, volcanoes erupted in two main regions (Figure 1C). Yet while Aboriginal Australian oral traditions have a demonstrably long reach, many having endured for several thousand years (Nunn, 2018), and include numerous memories of volcanic eruptions (Wilkie et al., 2020), no associated risk-management practices have been recorded. This is undoubtedly because such practices are sustained only when there is a constant threat, as at Merapi and Yasur (see above), whereas no Australian volcano has erupted for at least 4000 years. But in Aboriginal Australian cultures, there is little doubt that such risk-management practices would once have existed,[2] given that parallel practices for coping with more regular disasters (such as tropical cyclones) have been documented (McLachlan, 2003).

One of the lessons from such information is that there is no universally-acceptable way of managing volcano risk, however obvious this may appear to people schooled in the western rationalist tradition, so that the most effective future-focused management strategies in many non-western contexts are those that combine these two knowledges (Marín et al., 2020; Mercer et al., 2010). While scientific explanations of volcanism go unquestioned by most disaster managers, there are elements of traditional coping with volcanism that merit inclusion in downscaled management strategies. These include the cumulative experience of volcanism by local peoples, often over timescales of hundreds of years, that allow them to recognize precursors and to know what is likeliest to happen where, information that is often impossible to deduce from geoscience research alone; good examples come from the Pacific Islands where traditional memories of volcanism are far longer and more complete than those science can obtain (Németh & Cronin, 2009; Petterson et al., 2003).

Traditional earthquake responses

In the islands of the South Pacific Ocean, the demigod Maui was once considered to have created islands and to continue holding them in place (Nunn, 2003). The latter was of particular concern to people living on islands affected by volcanism and earthquakes, during which the land was prone to abruptly shift vertically and sometimes cause flank landsliding which, in the most extreme cases, might cause the entire island to ‘disappear’ beneath the ocean surface (Nunn, 2009). Within the islands of Tonga, where earthquakes are common, it was once generally believed that Maui kept the islands upright but that, being a person renowned for his laziness, was forever nodding off to sleep, a situation to be avoided in case a particular island should slip from his grasp in the process. An earthquake was widely considered to be a precursor of such an event. In 1865, the Reverend Thomas West noted that whenever there was an earthquake in Tonga, the people would

“invariably raise a great shout, during the continuance of the tremulous motion, for the purpose of thoroughly awakening the Plutonic deity [Maui], lest his nodding and uneasiness should, unhappily, overturn the world altogether” (1865: 114-115).

A comparable tradition was formerly practiced by the Anal and Lamgang peoples of northeast India who believed that another parallel world existed below the surface of the earth. As Lt-Colonel John Shakespear explained in his 1912 account, sometimes

“the people of the lower world shake the upper one to find out if anyone is still alive up there so, on an earthquake occurring, the Anal and Lamgang villages resound with shouts of ‘Alive! Alive’” (1912: 184).

A third example comes from southwest Canada where the Kwakwaka’wakw people once held the belief that earthquakes were “produced by ghosts” (Boas, 1891, p. 613) leading them to respond by making loud noises whenever they felt the earth shake.

The response by people to earthquakes involving shouting and making loud noises from these three quite different places may point to a once universal belief, now lost, about the causes of an earthquake and the ways in which people should respond to it, perhaps to prevent something worse happening in its aftermath.

This response would also have had practical benefits associated with the management of seismic risk. For instance, making noise would alert everyone to the occurrence of the earthquake, perhaps making sure that everyone was prepared for aftershocks. The response may also have had allowed community leaders to know from a lack of noise in particular places who might have been badly affected by the earthquake and therefore unable to respond and needing assistance: a rationalization of apparently unfathomable practice.

Traditional responses to coastal land loss

The end of the last great ice age was marked by a comparatively rapid rise of sea level, a net 125 m within 10,000 years, that altered coastal geographies in ways that would have challenged people living along the fringes of the land in every part of the inhabited world (Nunn, 2021). So transformational, maybe so traumatic, would the effects of this multi-generational sea-level rise have been that it is almost certain that these would have become subjects of enduring oral traditions, the residues of which are still found in some places (Nunn et al., 2021; Roberts et al., 2020).

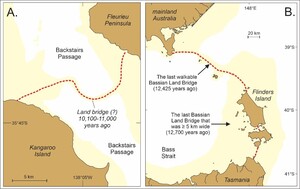

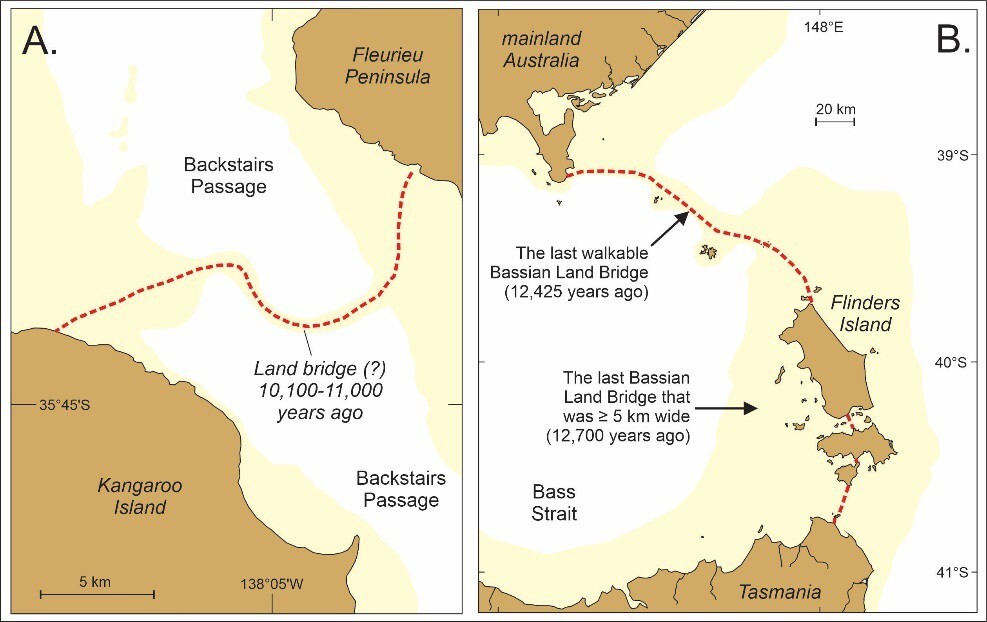

Among the best-preserved memories from this time are those from Aboriginal Australia where there are currently groups of stories from 34 locations all along the coast of this continent that recall times – in this case, more than 7000 years ago – about when the shoreline was further seaward, when lands that are now undersea were exposed and utilized by people, and when what are now islands offshore were contiguous with an adjacent mainland (Nunn & Reid, 2016; Reid et al., 2024). Well-researched examples come from Backstairs Passage, which today lies between mainland Australia (Fleurieu Peninsula) and Kangaroo Island, and from Bass Strait, which today separates mainland Australia (Gippsland) from Tasmania (Figure 2). The Ngarrindjeri stories about Backstairs Passage recall when a man named Ngurunderi was pursuing his two wives and, seeing them walking across this gap (when it was dry land), summoned the waves to come and drown them; the submergence of the last land bridge in Backstairs Passage is estimated to have occurred 10,100 years ago (Nunn et al., 2024). Palawa stories from Tasmania have been interpreted as memories of the time when the island was joined to Gippsland by a land bridge, the last remnant of which became submerged about 12,500 years ago (Hamacher et al., 2023).

The survival of such ancient stories as oral traditions passed across hundreds of generations points to the impactful nature of the events they recall, in these cases the loss of a land connection that halted interaction between peoples on adjacent landmasses, something that is likely to have been transformational in many of the world’s cultures (Nunn & Cook, 2022).

In these two examples, there is little information about the nature of people’s responses to land loss but elsewhere some has survived. These responses can be separated into practical and ritual ones, argued as analogous to modern climate-change adaptation and mitigation respectively.

Practical responses to land loss and shoreline erosion today include the construction of sea defences (seawalls), a key method of adaptation. In the past, people in Australia did similar things. For example, having witnessed the sea level rising for a long time and fearful it might eventually submerge all of Australia, the Wati Nyiinyii people of the Nullarbor coast (Western Australia) recall that they rushed to the coast and began “bundling thousands of [wooden] spears to stop the encroaching water … these bundles were stacked very high and managed to contain the water” (Cane, 2002, p. 91). This is likely to be an example of an artificial structure built to stop the encroachment of the sea onto the land, an expression of adaptation more than seven millennia ago.[3]

In contrast to such practical adaptation, there are examples from Australia and elsewhere of ancient mitigation, responses to sea-level rise that were believed at the time to address its causes. The existence of such mitigatory responses can be inferred from the presence of purposive stone arrangements along coasts that have interpreted as evidence for the “ritual control of extreme tidal regimes” (McNiven, 2008, p. 155) and perhaps, more than 7000 years ago, the control of rising sea level (Nunn, 2021). Stone arrangements along the coasts of France have been interpreted in similar ways, it being argued that the thousands of linearly-organised standing stones (menhirs) at Carnac were created “as a cognitive barrier … that could stop, impede, or filter movement or passage” between the spiritual and material worlds, specifically to halt the damaging rise in sea level in the Gulf of Morbihan about 6200 years ago (Cassen et al., 2011, p. 100).

The evident/inferred maturity of both adaptation and mitigation to climate change by people thousands of years ago points to the degree of ‘ecoanxiety’ that they must have experienced, underlying the trauma involved in living with constant environmental change, but also providing lessons for future human responses to climate change (Nunn, 2020).

Conclusion: enhancing contemporary risk management through ancient practice

While climate change and other disasters discussed in this paper were stressors of many pre-modern societies, the practices they evolved to cope with these phenomena are not readily transferable to today. First, there are many more people on earth today, living more complex and interdependent ways of life that can be more readily up-ended by external stressors than was the case in most pre-modern contexts. Second, in today’s world the pace of recent and projected climate change is faster than that which our ancestors experienced. This does not render their knowledge and coping strategies irrelevant but is does mean that they are not uncritically fit for the purpose of coping with the future in particular places. The way forward lies in blending knowledges to optimize their applicability as well as their acceptability to culturally-diverse populations.

Efforts at blending traditional (culturally-grounded) and modern (science-derived) knowledges have advanced in several parts of the world (Gauvreau & McLaren, 2016; Mercer et al., 2010) and are starting to inform the development of global strategies for disaster education and response; a good example is the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 that calls explicitly for holistic indigenous disaster risk reduction research (Ali et al., 2021).

Perhaps the greatest demonstrations of the utility of knowledge blending for understanding disaster history come from the northwest USA and southwest Canada, a comparatively long-settled region where disasters derived from earthquakes (including tsunami) and volcanism are relatively common (McMillan & Hutchinson, 2002); an example is the 5600-year old destructive Osceola Mudflow from Mt Rainier, which is recalled in both story and science (Nunn, 2018; Vallance & Scott, 1997). Similar research has led to more realistic tsunami exposure modelling in the Pacific Islands and New Zealand (Goff et al., 2011; Goff & Nunn, 2016).

Yet despite these examples, the richness of non-western knowledges for disaster coping in particular places remains largely excluded from contemporary disaster risk reduction strategies and practice. Greater acknowledgement by (western-trained) scientists and disaster professionals of traditional/indigenous knowledges would inevitably result in more effective strategies, not just in terms of their applicability to particular places but also in terms of their acceptability to the peoples living there. No-one wants to hear that their ancestral knowledges are worthless, especially when they are not.

I simplify to make a point about instinctive human attitudes towards risk, recognizing that the reality is far more complex (Brown, 2019).

One account of a volcano in South Australia recalls how an Aboriginal warrior once stopped the volcano from “belching” by driving the “devils out of it” and “subdued it, made it our friend, and it has lost its wrathfulness” (Wilkie et al., 2020, p. 8).

The remains of a submerged seawall, >100 m long and constructed 7000 years ago to protect the community of Tel Hreiz (Israel), is the earliest-known surviving coastal defence against sea-level rise (Galili et al., 2019).